Leica 100th Anniversary “Gotcha questions”

December 31, 2025

McNeil in the darkroom with his favorite Leica IIIF, which was used for many of his photographs over the decades.

Capture the moment or carefully compose?

Larry: ‘Capture the moment’ because we can’t put life on pause. Well most of us can’t, so we wing it with our cameras and do what we can. Shoot some quick sequences and cross our fingers that we got it.

On the other hand, we all carefully compose whether we admit it or not. Even when we only have a second to capture and create the image. I’d assert that the compositions are how we perceive, and how we visually emphasize what we see. We’re saying something with our photographs, and the only way to do that is to compose it.

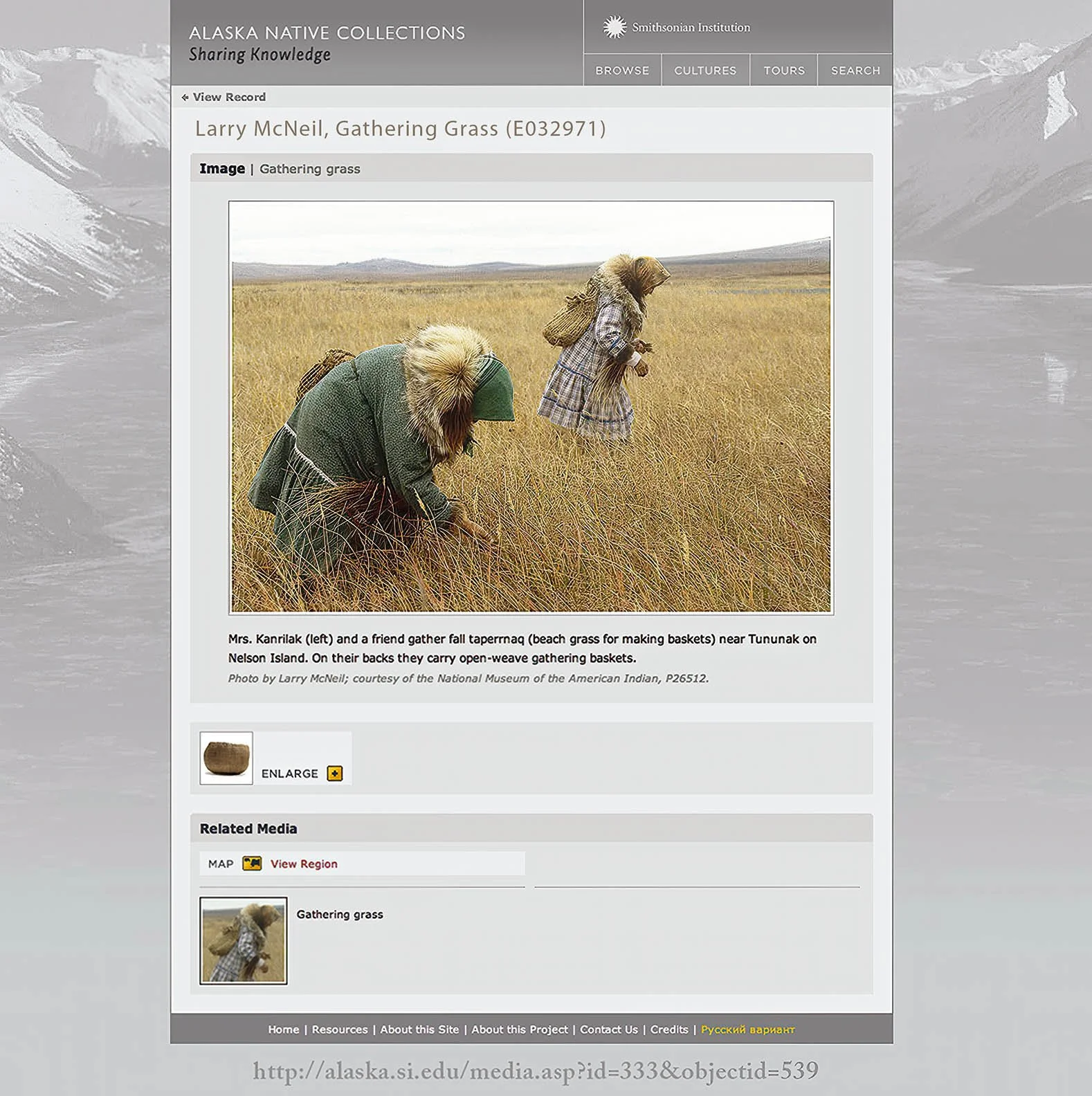

For this project about Yupik women picking grass for their baskets in Western Alaska, it was definitely about capturing the moment because it was unfolding so quickly. There was no time to fuss with posing or getting a lot of variations of the scenes. Not only that, the shutter on all of my SLR cameras were loud and so distracting that the women would glance over at the sound of the shutter firing, which made the photos look staged. I knew this shortcoming and brought my Leica IIIF, which is nearly completely silent. I ended up shooting most of these scenes with the quiet rangefinder I’d been using for years. The Smithsonian acquired a number of these photographs for their collection.

I absolutely love shooting with the Leica IIIF because the 50mm lens is sharp and using it becomes fast and intuitive. I can quietly step in closer and not bother the people I’m photographing. This was not long before the M6 was released and I’d been using this IIIF since the start of photography school, so I was very attached to it and knew what it could do. For this composition I wanted a shallow depth of field with the background blurred and Mrs. Kanrilak sharp. That’s where f/2 comes into play with capturing the moment.

Capturing the moment means seeing precisely how we do it. Leica has what feels like a lens for the ages, a 50mm Summitar f/2 (fairly fast for 1955). The Ernst Leitz engineers (Oskar Barnack?) designed a lens that was optimized for high quality negatives and making it compact for travel. Capturing the moment means being on the road, and the innovative lens slides into the camera body when you put it away. That’s timeless innovation. I was shooting a lot of the newly improved Kodak Ektachrome E-6 film in the early 80’s and being able to shoot at f/2 in dim light made this camera and lens combination good for continued use, even as more modern cameras were available.

In 1975 I used the Leica IIIF for school assignments because I wanted to learn photography with a classic camera. It took a bit of practice to get used to the rangefinder, but I liked how it slowed down your shooting style and you had to be more careful with your compositions. It harmonized with our new way of using mindfulness with our creativity with learning photography. It felt like I was slowing time yet capturing the moments as they presented themselves. We were assigned still life photographs, which was new to me, and this camera was useful for previewing what the photos would look like. The viewfinder was bright in darkened studios. This was where we had to shift to carefully composed photos in a studio.

This was my first studio still life photo made at the photography school in 1975. I discovered that I had a natural talent for still life photography. It came from noticing everyday scenes, such as seeing my glasses sitting on a record player with dramatic low light. I went to go get the camera and I used the Leica as a kind of “visual notepad” for assisting with the studio work later. The scene only looked like this for about five minutes each day and the light changed. It was a careful composition based on capturing the moment, which is pretty much how I still do creative work.

One lens for the rest of your life, which one?

Larry: The 35mm because it closely matches how we see the world. The perspective matches our natural vision and it feels right. I shot with the Leica R3 for years because it could make exposures so precise that even the fussy Kodachrome was correct with the Copal shutter and light meter. As a studio shooter we got used to a “normal lens” because the perspective is natural for accurate views, but I do a lot of photography outside of the studio too, which is when the 35mm essentially lives on the main camera. Yes, definitely the 35mm because it is on the wide end of the “holy trinity” (wide, normal and short telephoto) of prime lenses. A lot of my well known photographs over my career were made with the 35.

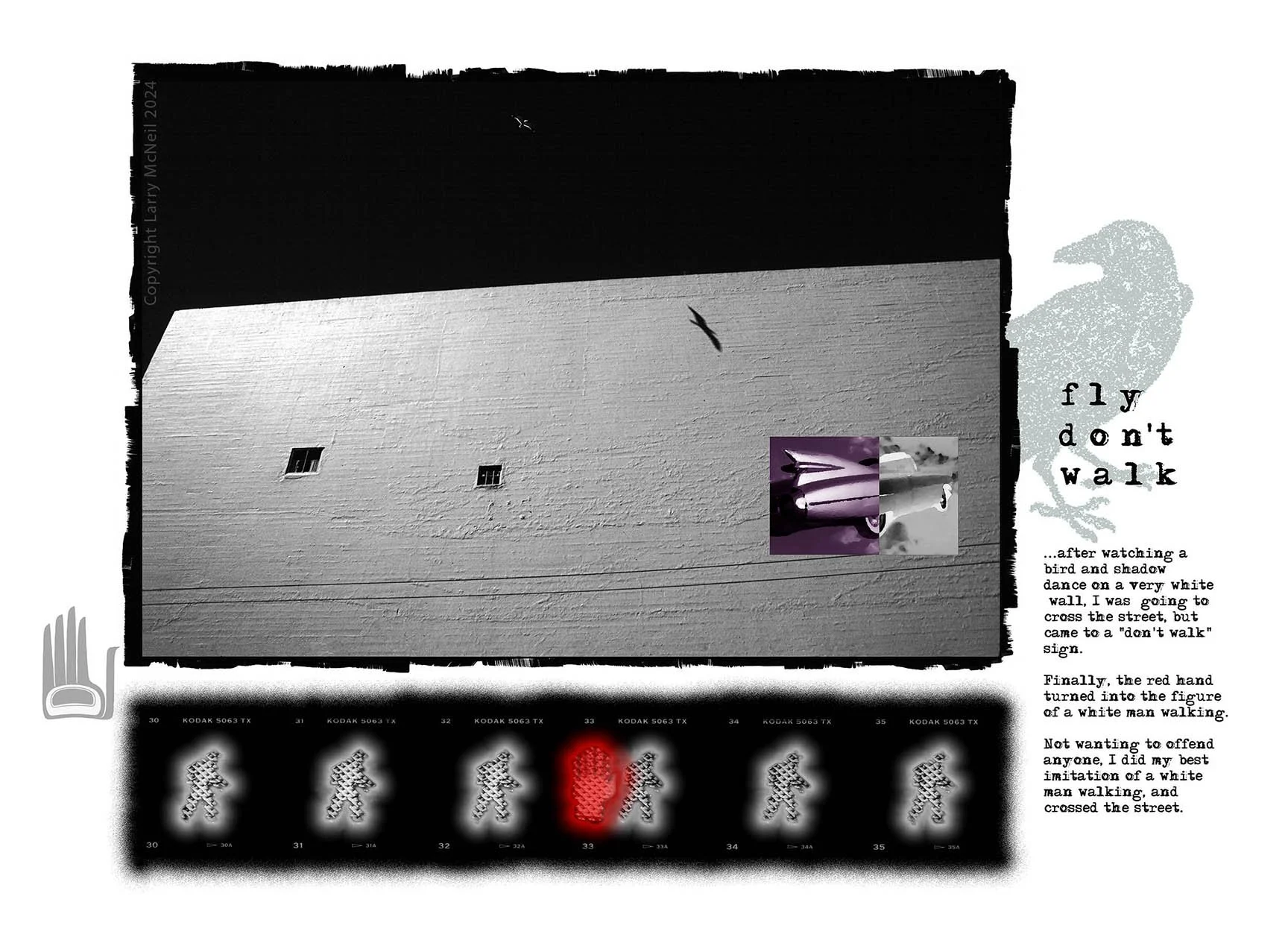

Street photography is in a lot of my film and digital photography and I’d carry my camera under my jacket while walking cities. I’d noticed this building in San Francisco while getting off the subway (BART) downtown. The light looked dramatic for about half an hour each day and the 35mm was perfect, especially with ISO 64 Kodachrome which rendered the sky a very dark blue when exposing for the highlight on the brightly painted white building. The two tiny windows added an air of mystery and when I shifted this to a black and white palladium print, the sky turned black, which is exactly what I’d hoped. My style had shifted to humorous narratives and I continued with the layered look from years earlier. At any rate, it was good to continue using my favorite 35mm lens with the newer looks I was experimenting with. This is titled “Fly don’t Walk” from 1998.

I know you didn’t ask, but I’ve been gravitating towards wide angle lenses again (as I liked early in my career). This ultra-wide 15mm lens lives on the M6 these days. I like how it has become as easy as a “point & shoot camera” in that I don’t have to focus it because it has such a deep depth of field. The external meter is for shooting in the desert bright sun with the M6, which has become my favorite 35mm film camera. For street photography you just wrap the neck strap around your wrist so it doesn’t fall and this becomes a very fast camera where capturing the moment is very, very fast. I match the camera settings to the light and don’t have to fuss with any camera controls, which is notable for a rangefinder film camera. Since film has become so expensive, hardly any shots are wasted from inaccurate exposures and contact prints look excellent.

Color or black and white?

Larry: I instinctively return to black and white all the time and likely shot more b&w film in my life than color. It’s poetic and forgiving. I’ve lost track of all the b&w I’ve shot with the Q2 Monochrom the past couple years. A million shots? Something like that. A lot, more like 1.2 million exposures with this cool camera. The highest priced photo I’ve sold was a b&w palladium portrait. On the other hand, I keep shooting color (with other cameras of course) hoping to match the magic of Kodachrome, but we’ll see. I seem to go in phases of b&w for a couple of years with very little color shot.

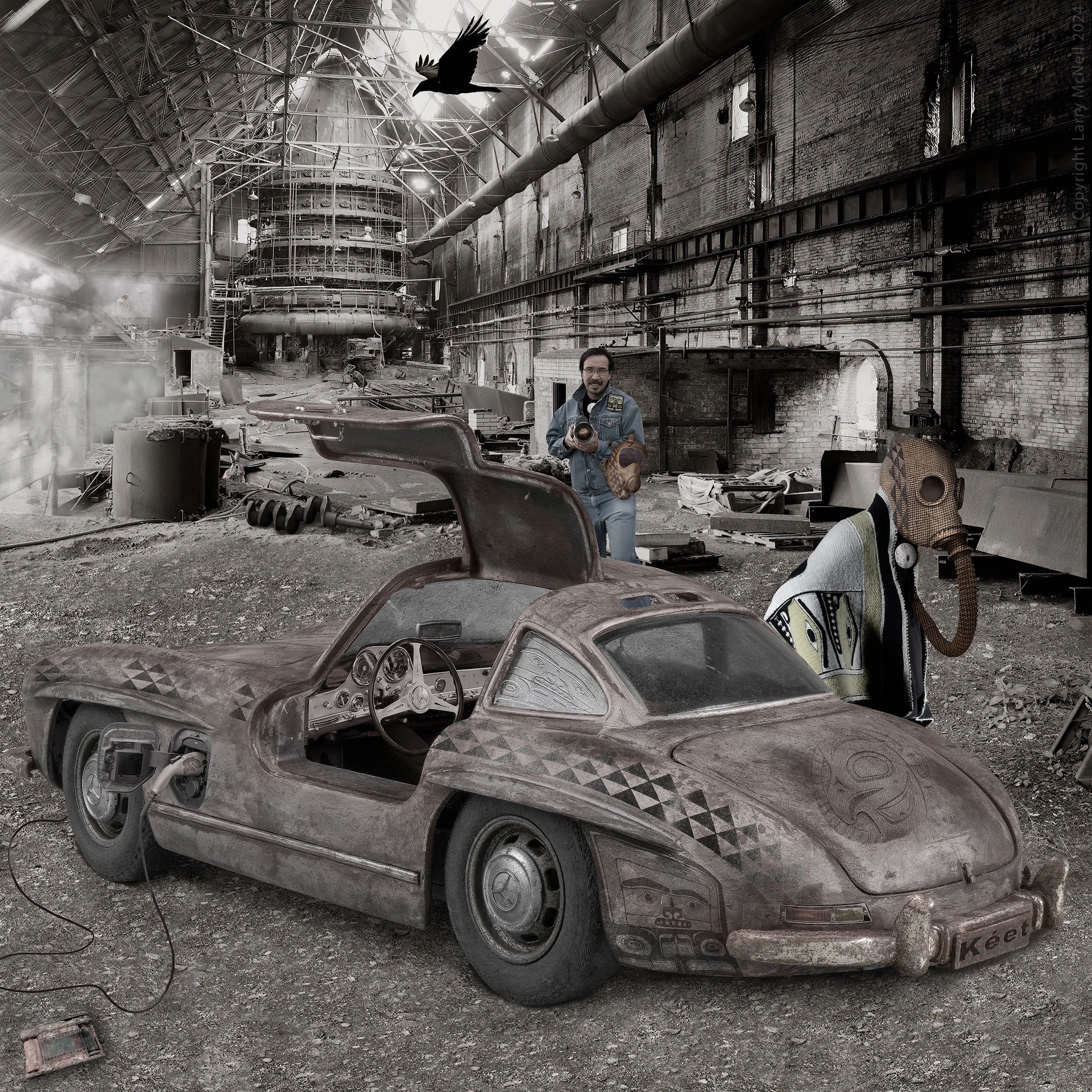

This was a composite of b&w photos shot mostly with the ultra-sharp Q2 Monochrom camera. The Q2 can only shoot in monochrome and I love using it in the studio with strobes. The Mercedes gull-wing was colorized to match the subdued brown shift of the abandoned steel mill. It is titled, “Climate Chaos, Ḵutí Xʼóolʼ 2055,” or “Climate Crisis 2055” for short. The quality is so good that this may be made mural sized and it will hold together. My creative process involves writing in a journal and if the entry is captivating to me, I’ll make a photograph based on the narrative. I’d visualized this in b&w because of the feel of the story. It has colorized characters, another tactic I started using in the days of film.

“Tonto’s Earthen House” was all about color and the climate chaos. The Cadillac is what our Tlingit Nation calls “Chilkat Blue” and is at the center of our ancient and contemporary art. It is nearly a turquoise color and I wanted a composition that had only a few essential colors that felt sumptuous yet also served as a layer of meaning.

Do you think gear matters?

Larry: That’s a yes & no answer because a gifted photographer’s super powers comes from their heart and soul, not the camera they’re holding. On the other hand, there ain’t nuthin’ like a sharp lens and well- designed camera to make your heart beat a little faster. There’s the “holy trinity” of lenses too and the right one is the one that gets the looks you’re seeking. Lighting is such an essential part of photography and we eventually find ourselves using some kind of lighting that enhances the feel of our photos. In the film era some of us needed various camera format sizes and even had film preferences and darkroom chemicals that also got the looks we were seeking. With all the gear swirling around sometimes we reach a saturation point and just use one camera and one lens for a while. That’s where I’m at right now, especially after a career of lugging lots of camera bags and cases for projects. When I travel these days, I only allow myself one small camera bag and I really like that. So maybe part of the answer is we bounce back and forth between having specialty gear and when we’re fed up with that, shift towards a minimalistic ethos.

Who’s your inspiration?

Larry: Lee Marmon for helping break a path for future Indigenous photographers and for finding beauty in the chaos. Eugene Smith for his poetic sensitivity to light with capturing brutal war scenes and environmental chaos. Imogene Cunningham and Edward Weston from the sassy Group F/64 for living by their wits to flush old ideas down the tubes. Margaret Bourke White dominated photojournalism in the 20th century and inspired people like George Lucas with his view of the planet Coruscant, and her view looking down at the skyscrapers of New York City with a silver DC-4 flying opulently in the foreground.

What’s your most memorable moment in photography?

Larry: Driving through the December snowflakes on old Route 66 in New Mexico and unexpectedly coming upon an offbeat scene that was simultaneously amusing and culturally relevant. It was a wall sized 1930’s tourist sign that asserted “REAL INDIANS” were here, beckoning tourists to come off the road and browse the wonders of the Southwest. It inferred that the tourists have been only meeting fake Indians up to now, and to prepare themselves for the real deal. That one photograph changed my life forever and allowed me to go rogue with photography and to break rules while still being assertive. It still breaks the ice and helps me find my way.

Any advice for young up-and coming photographers?

Larry: Follow your instincts with compositions and content, don’t think too hard in the moment. The creative process is fleeting and slippery, it wants to get away and you’ve got to affirm and hold fast to your personality and character with your creative work. That’s another way of saying “be your authentic self” because this will always be your best work. Keep making work no matter what, especially when you’re in survival mode and are struggling. Don’t give up when things get tough. Listen to the advice of others but know when to follow your own path. Mentors are good to find, as is interacting with other creatives. Have fun experimenting and try something unexpected and if it looks bad, so what? Learn from what doesn’t work too, that’s also an important part of the process, to crash and burn.

The hockey player Wayne Gretzky had the perfect saying that applies to photographers too; “You miss 100% of the shots you don’t take.” Take the shot. Or if your process is a little more studied, make the shot. Build it from scratch if that’s your path. Enjoy the journey.

All content Copyright Larry McNeil, all rights reserved.